[an error occurred while processing this directive]

New Excavations at the Brough of Deerness: Power and Religion in

Viking Age Scotland

James H. Barrett1,* and Adam Slater2

Abstract - The grass-covered top of the Brough of Deerness, a small sea stack in Orkney, Scotland, holds the remains of

a substantial Viking Age settlement and associated chapel. The chapel was excavated by Christopher Morris in the 1970s

and discovered to have two phases, one above and one below an Anglo-Saxon coin minted between 959 and 975. New

excavations of two buildings from the surrounding settlement aim to illuminate the function of the site, and to inform our

understanding of the relationship between power and religion during the Viking Age diaspora. At least one of the buildings

was a domestic dwelling, of typical Scandinavian style, abandoned in the 11th to 12th centuries. However, both structures

represent only the top of a long stratigraphic sequence, with underlying middens radiocarbon dated to as early as the 6th to

7th centuries A.D. In its latest phases, the site was probably a chiefl y stronghold (as previously suggested by Morris) with

a symbiotic relationship with surrounding farms. In this preliminary report on new research, several models are tentatively

proposed to account for the role of such a settlement within the political economy of late Viking Age Scotland.

1McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge, CB2 3ER, UK.

2Cambridge Archaeological Unit, Department of Archaeology, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2

3DZ, UK. *Corresponding author - jhb41@cam.ac.uk.

Introduction

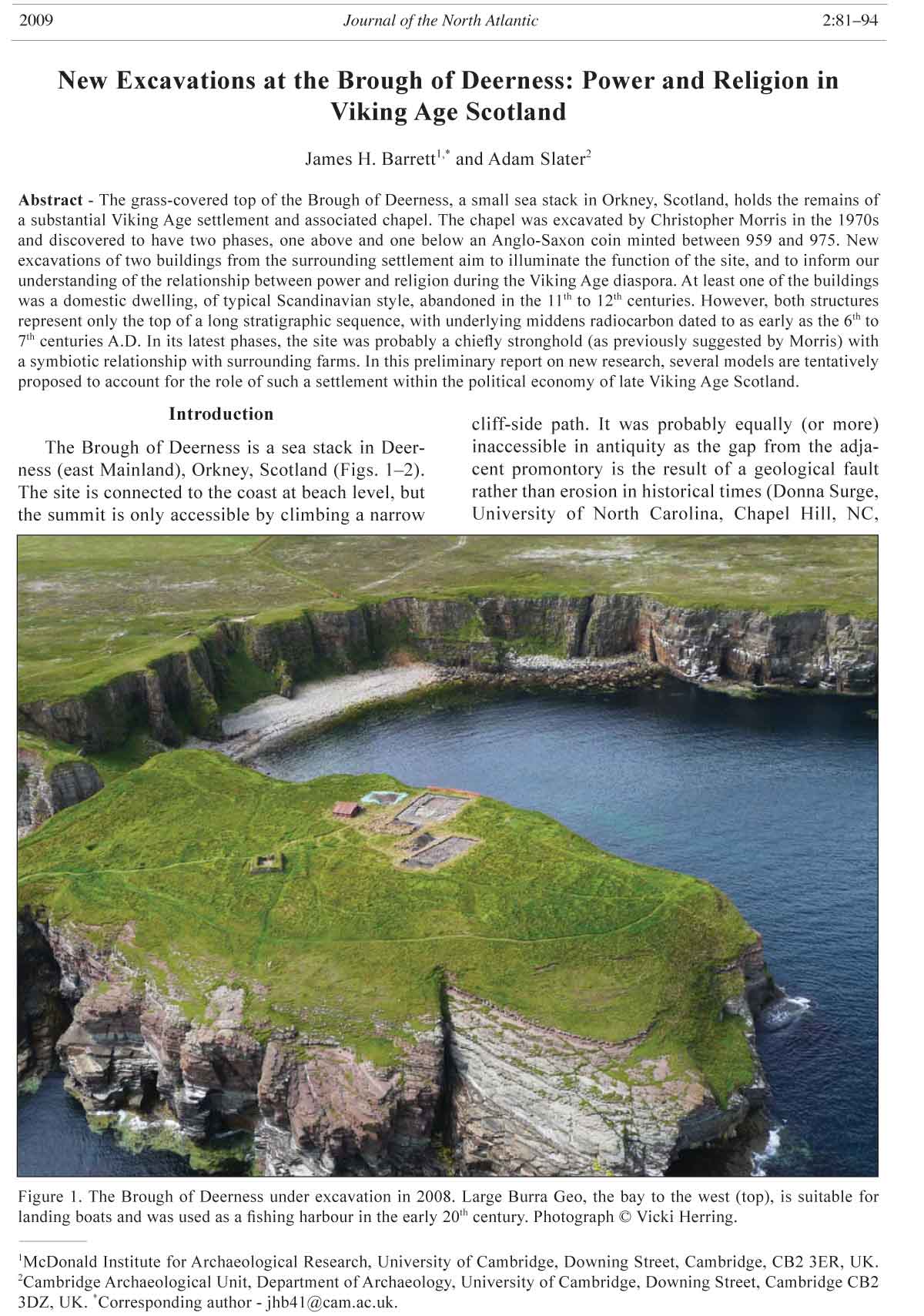

The Brough of Deerness is a sea stack in Deerness

(east Mainland), Orkney, Scotland (Figs. 1–2).

The site is connected to the coast at beach level, but

the summit is only accessible by climbing a narrow

cliff-side path. It was probably equally (or more)

inaccessible in antiquity as the gap from the adjacent

promontory is the result of a geological fault

rather than erosion in historical times (Donna Surge,

University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC,

2009 Journal of the North Atlantic 2:81–94

Figure 1. The Brough of Deerness under excavation in 2008. Large Burra Geo, the bay to the west (top), is suitable for

landing boats and was used as a fi shing harbour in the early 20th century. Photograph © Vicki Herring.

82 Journal of the North Atlantic Volume 2

USA, pers comm.). The Brough’s grass-covered top,

surrounded by ca. 30-m cliffs, holds the remains of

an enigmatic settlement—including a chapel and approximately

30 associated buildings—traditionally

interpreted as a monastery or chiefl y stronghold

(Fig. 3). Despite evidence that the stack was used for

target practice in the First and Second World Wars

(Morris and Emery 1986 and references therein), the

outlines of many house foundations remain at least

superfi cially intact.

Past archaeological excavation, directed by

Christopher Morris (Morris and Emery 1986), focused

on the area around the partially upstanding

stone chapel (Fig. 4). Under it was discovered the

remains of an earlier timber chapel, predating a

layer containing an Anglo-Saxon coin (of Eadgar)

minted between A.D. 959 and 975. This chapel is

thus among the earliest known evidence for Viking

Age Christianity in the Scandinavian North Atlantic

region—possibly predating the traditional conversion

date of A.D. 995 (Barrett 2002, Morris 1996a).

At least the timber phase was potentially founded in

the 10th century, accepting that the coin could have

been old when deposited. The overlying stone phase

may have been built in the 11th or 12th centuries, based

on a radiocarbon date of A.D. 1030–1249 (calibrated

at the 95% probability level) on human bone from

a grave that post-dated its construction (see Barrett

2002). The stone chapel is unlikely to date as late as

the 13th century because the entire site seems to have

been abandoned by then. For example, most of the

medieval pottery known from the Brough of Deerness

came from the decay and collapse phases of the chapel

(Barrett and Slater 2008, Morris and Emery 1986).

Although unique in many respects, the site belongs

to a group of early historic (defi ned as the 6th to

12th centuries A.D. for present purposes) islet, promontory,

and stack settlements known from the Northern

Isles, other parts of coastal Scotland, and the Irish

Sea province. A simple typology might classify them

along scales of size and accessibility on the one hand

and secular versus ecclesiastical function on the other.

In terms of size and access, they range from small

low-lying islands such as Iona (O’Sullivan 1999) to

tiny inaccessible stacks such as the “Castle” of Burrian

in Orkney (Fig. 5; Moore and Wilson 1998). In

terms of function, interpretations

tend to vary from aristocratic

strongholds to monasteries—with

the interrelatedness of power

and religion in the early historic

period allowing for ambiguity between

the two (cf. Barrowman et

al. 2007, Morris 1996b).

It is clear that some sites

served as centers of chiefl y power.

Examples include Burghead and

Dumbarton Rock in Scotland and

St. Patrick’s Isle, Peel, on the Isle

of Man. These settlements have

been associated with the kings of

Pictland (Ralston 2004), Strathclyde

(Alcock 2003), and Man

(Freke 2002), respectively. Others

were clearly monastic in focus.

Well-known Scottish examples

include Iona (O’Sullivan 1999)

and Inchmarnock (Lowe 2008).

In the Northern Isles, the bestknown

site is the Brough of Birsay

(Fig. 6). It is a relatively large tidal

islet off the northwest coast of

Mainland, Orkney. Historical evidence

indicates that in the 11th century

it was either the primary seat

of the earls and bishops of Orkney

or part of a multi-focal settlement

(including mainland sites) that

collectively included these funcFigure

2. Northern Scottish sites mentioned in the text. tions (e.g., Crawford 2005, Morris

2009 J. Barrett and A. Slater 83

1996b). Based on archaeological evidence, its role

as a central place may have begun in Pictish times. It

has seen a series of major excavation campaigns (e.g.,

Curle 1982, Hunter 1986, Morris 1996c).

At the other end of the scale, the small inaccessible

sites of the Northern Isles have only occasionally

been the focus of excavation—for understandable

reasons given the logistical problems they

Figure 3. The Brough of Deerness as surveyed by Fred Bettess during the 1970s excavation (Morris and Emery 1986), when

grazing by sheep revealed the outlines of more buildings than can be seen today. The 2008 excavation areas are superimposed.

(We are grateful to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland and Christopher Morris for permission to reproduce this plan).

84 Journal of the North Atlantic Volume 2

present. The Kame of Isbister in Shetland, where

the outlines of approximately 20 small buildings

have been recorded, was even investigated as part

of the television series Extreme Archaeology, which

sponsored excavation in difficult locations (Anonymous

2003). This work produced a Viking Age

radiocarbon date on charcoal, but no artifacts were

found to further aid interpretation. Raymond Lamb

(1973), once the Orkney Archaeologist, resolutely

surveyed many sites of this kind and was a particular

advocate of a religious model—interpreting

them as isolated monastic hermitages (either of the

Figure 4. The stone chapel at the Brough of Deerness, as consolidated following excavation by Christopher Morris from

1975 to 1977. Photograph © James Barrett.

Figure 5. The Castle of Burrian—a rock stack in Westray, Orkney, that has two house foundations perched on top. It is an

example of the smallest of such sites in Atlantic Scotland. Photograph © James Barrett.

2009 J. Barrett and A. Slater 85

early “Celtic” or later medieval traditions). However,

other interpretations are also possible.

Some small sites may actually, as Lamb (1980)

conceded, represent earlier Iron Age occupation of

limited relevance to the present discussion. Others

may have functioned as defensive refuges and/or

“watch-towers” of early historic date. Small promontories

were used for this purpose in the 12th century

based on both the Orkneyinga saga (composed ca.

1200) (Guðmundsson 1965) and surviving ruins such

as the castle of Old Wick in Caithness (Gifford 1992).

This tradition continued for centuries. Bucholie

Castle, near Freswick in Caithness, is a good example.

It is a 15th-century fortifi cation on a tiny promontory

that may also be the site of the stronghold and

lookout post known as Lambaborg in the Orkneyinga

saga (Barrett 2005, Batey 1991, Gifford 1992; cf.

Barrowman 2008 regarding Dùn Èistean in Lewis).

These northern promontory, stack, and islet

sites—large and small—have the potential to offer

important clues regarding the relationship between

power, religion, and migration (perhaps better understood

as transnationalism—allowing for complex

movement to and fro along networks; see Barrett

2008a, and references therein) in the early historic

period. This is so whether they were centers of “Scandinavian”

lordship, often with associated churches

(as at the Brough of Birsay and St Patrick’s Isle), or

earlier monastic communities welcomed by chieftains

or kings inspired by the example of Christianized

regions such as Ireland and Gaelic Dál Riata in

western Scotland (cf. Carver 2008, Dumville 2002).

In order to realize this potential, it is necessary

to answer two basic questions: what was the chronology

and function of these sites, singly and as

classifi ed groups? Only with these answers in hand

will it be possible to address more complex issues.

For example, did early monasticism precede or follow

other possible “Irish” cultural infl uence—such

as ogham writing (Forsyth 1995) and fi gure-ofeight

buildings (Ralston 1997)—in pre-Viking Age

Orkney? Or later in time, was the adoption of an

indigenous religion—Christianity—by chieftains

of Scandinavian descent of central importance to

the creation of powerful principalities such as the

Earldom of Orkney and the Kingdom of Man? More

holistically phrased, what was the role of religion in

the processes of migration, transnationalism, and the

resulting emergence of new polities?

These questions need to be addressed one site at a

time, setting the evidence from careful stratigraphic

excavation into its wider regional and international

context. The Brough of Deerness is a promising case

study given the combination of a chapel and approximately

thirty associated buildings. During fi ve

weeks of fi eldwork in June and July of 2008, we set

out to explore the state of preservation, chronology,

and function of the site—focusing on the buildings

around the chapel. These have never before been

excavated. What follows is a preliminary description

and interpretation of what was found. It must be read

as an interim statement regarding work in progress.

The Excavation

The Brough is not presently grazed and is thus

overgrown with thick tussocks of turf that hide

low-relief surface topography. Nevertheless, a

Figure 6. The Brough of Birsay—a tidal islet off the north-west coast of Mainland, Orkney. In the 11th century, it was either

the primary seat of the earls and bishops of Orkney or part of a multi-focal settlement including these functions. Photograph

© James Barrett.

86 Journal of the North Atlantic Volume 2

reasonable guide to the location of structures was

provided by aerial photographs from the 1970s, the

1977 earthwork survey (Fig. 3), and both gradiometer

and resistance surveys conducted by the Orkney

College Geophysics Unit in 2006 (Moore 2007,

Ovenden 2008). It was therefore possible to locate

probable building foundations, two of which were

selected for excavation in consultation with Historic

Scotland and the Orkney Archaeologist.

Area A, an intervention of approximately 13.6 m

by 5.8 m, was opened over Structures 23 and 24

as recorded in 1977 (Fig. 3). Structure 23 was not

visible on the surface in 2008, but Structure 24 was

clear as a raised semicircular feature with a diameter

of ca. 4 m. Area A was chosen to:

1) include a building (Structure 23) on the eastern

side of the main trackway running through the

settlement;

2) section what was thought might be a large shellhole

from use of the Brough for target practice

during the First or Second World Wars (Structure

24);

3) include a region of intense geophysical anomaly

and “busy” topography towards the north end of

the Brough. This area clearly has multi-phase

settlement, so it was considered a good place to

begin to look for any pre-Viking Age evidence;

and

4) be well placed for possible later extension, either

southward to include Structures 18 and 19

or eastward to include Structure 25. Structures

18 and 19 are centrally located within the settlement

and oriented at 90 degrees to most of the

other ruins on the Brough. Together they comprise

one of the longest visible house foundations.

The building they represent may thus have

held special importance within the settlement.

Structure 25, if not two contiguous shell-holes,

appears to be curvilinear and may thus represent

a building of Iron Age/Pictish style.

Area B, an intervention of approximately 14.6 m

by 9.8 m (Fig. 3), was opened over Structure 20, one

of a series of parallel buildings along the main path

running through the settlement. Before excavation,

it was thought likely to be single-phase, based on the

clarity of its outline in the earthwork survey, resistance

survey, and aerial photographs. It was chosen to:

1) include a building on the western side of the

trackway;

2) represent a region of less intense geophysical

anomaly and less uneven topography towards

the west and south of the Brough;

3) rescue archaeology close to the cliff edge which

could nevertheless be made safe for both excavators

and visitors; and

4) uncover a house that might be immediately interpretable

after a brief trial-excavation, rather

than obscured by many superimposed phases.

Area A

The 2008 excavation of Area A revealed the general

outline of Structure 23 and demonstrated that

what was recorded in survey as Structure 24 was a

palimpsest of superimposed ancient features rather

than a single building or a large shell-hole from the

First or Second World Wars (Figs. 7–8.)

Structure 23 appears irregular in plan, partly

due to post-abandonment collapse but apparently

also because it was inserted into a space framed by

pre-existing buildings and/or ruins. It was approximately

7.2 m by 3.5 m in internal dimensions. It had

an inner wall face of unbonded masonry, partly cut

into pre-existing deposits and partly set in what was

Figure 7. Plan of Area A showing the destruction phase of Structure 23 and the earlier (radiocarbon dated) middens and

features beyond its eastern end. Image © Vicki Herring.

2009 J. Barrett and A. Slater 87

otherwise an earth and rubble foundation (presumably

for a turf superstructure). Its bioturbated upper

fl oor level included much charcoal. A single small

shell-hole was discovered near the middle of the

building, associated with fragments of shell-casing.

Structure 23 may have had two opposing doorways

near its western gable, but it was not excavated after

we exposed its general outline, so this interpretation

is conjectural. Most work in 2008 focused on the

eastern end of Area A and on Area B (see below).

Structure 24 turned out to be a series of in situ

features of differing dates. The lowest of these were

midden deposits (with good preservation of animal

bone) into which Structure 23 was inserted. The

middens were examined within the constraints of a

small 2-m by 1-m sondage, and were found to overlie

earlier structural features. No diagnostic artifacts

were recovered from Area A, but two samples of

animal bone have been radiocarbon dated to help

guide ongoing excavation. They came from the uppermost

and lowermost excavated contexts of the

middens into which structure 23 was built. These

samples produced dates of A.D. 660 to 870 (sample

SUERC-23655, 1260 ± 35bp) and A.D. 570 to 665

(sample SUERC-23654, 1420 ± 35 bp), respectively,

at the 95% probability level. Neither of the dates

requires marine reservoir correction, being on pig

and cattle bones having δ13C values of -20.7‰ and

-21.6‰ (cf. Barrett and Richards 2004). They imply

the existence of a pre-Viking Age Pictish settlement

on the Brough of Deerness. It remains to be established,

however, whether or not there was continuity

between this ca. 6th- to 9th-century use of the Brough

and the later settlement.

Area B

The 2008 excavation of Area B demonstrated

that Structure 20 (hereafter “House 20”) was a

multi-phase house of Viking Age Scandinavian

style that was abandoned in the 11th to 12th centuries

(Figs. 9–10). It was approximately 10.4 m by 4.1 m

in internal dimensions (after narrowing from a probable

original width of approximately 4.9 m). House

20 overlaid an earlier feature—possibly another

building—the remains of which

were found extending from under

its southeastern corner.

The earliest construction

and occupation phases of House 20

itself have not yet been excavated.

In its penultimate configuration,

however, the building was a threeaisled

house with two rows of roofsupporting

posts and probably also

an internal cross-wall of perishable

material dividing its internal space

into eastern and western rooms. Its

eastern room contained a central

hearth, side aisles (marked out

by the roof-supporting posts and

small edge-set stones) and niches

in the northeast and southeast corners

(also demarcated by edge-set

stones). At some point, a second

hearth was also established near

the eastern end of the building. The

western room was mostly featureless,

but may originally have had

side-aisles. The fl oors associated

with this penultimate phase of the

building’s use produced a glass bead

of 11th-century date. Additional

fi nds from the exterior of House 20,

or from the destruction of its walls,

may be broadly contemporary with

use of the building (if not residual

from earlier Viking Age occupation).

These included a soapstone

Figure 8. The destruction phase of Structure 23 from the southeast. Photograph loom weight and a soapstone vessel

© Brian Rahn.

88 Journal of the North Atlantic Volume 2

of the northern wall (Fig. 13). The northern wall itself

was a rebuild, the original having collapsed earlier in

the life of the house.

shard—the latter of Norwegian style (Figs. 11–12). It

is probable that there were originally two entrances

into the building, in the northwest and northeast ends

Figure 9. Plan of Area B showing the penultimate occupation phase. Note the eight decommissioned post-holes (some

packed with stones) from the original internal roof supports. Image © Vicki Herring.

Figure 10. House 20 in Area B. Photograph © Brian Rahn.

2009 J. Barrett and A. Slater 89

north and south walls. Thus, the life of this single

building encapsulates a change in Scandinavian

architectural fashion dated to the 10th–11th centuries

in Denmark and Norway (if a few centuries later in

Iceland, at least in outbuildings) (Gestsson 1959,

Hvass 1993, Norr and Fewster 2003). Concurrently,

a new entrance was inserted in the center of the

south wall, and a new earth floor with occasional

paving slabs was laid. At this time, or shortly after,

a copper alloy pin of 11th to 12th century date

Late in the use-life of House 20, the internal

posts were removed and their post-holes filled in.

At the western end of the building, this entailed

digging and refilling relatively large and irregular

robbing pits—suggesting that the upright timbers

were very substantial in this part of the house. Elsewhere

the removal of the roof supports left more

discrete post-pipes that were backfilled with earth

and stone. The internal posts seem to have been

replaced with timbers along the inside edge of the

Figure 11. A soapstone loom weight from outside House 20 (scale in cm). Photograph © James Barrett.

Figure 12. A soapstone vessel shard from outside House 20 (scale in cm). Photograph © James Barrett.

90 Journal of the North Atlantic Volume 2

Figure 13. Northeast entryway to House 20, with internal and external threshold stones and fl agstone path. Photograph ©

Vicki Herring.

Figure 14. A selection of fi nds from House 20, including an 11th–12th-century copper alloy pin, a soapstone spindle whorl,

and the single piece of pottery from the building (spindle whorl diameter = 3.5cm). Photograph © James Barrett.

2009 J. Barrett and A. Slater 91

far), small, and discrete. In areas of deep stratigraphy

(where cultural deposits buffer the natural soil

acidity), bone is well preserved.

Secondly, the settlement was long-lived. The

uppermost layers of House 20 probably date to the

11th to 12th centuries, but it has numerous successive

fl oor layers and was remodelled at least twice.

Although we have not yet reached the earliest levels

of this house, its multiple phases point to a long period

of use. Moreover, it appears to have been built

on top of an earlier building, part of which extends

from under its southeast corner. House 23 has not yet

been investigated in such detail, but it too overlies

pre-existing deposits. It appears to have been dug

into middens of ca. 6th to 9th century date.

Thirdly, the settlement was a focus of domestic

occupation. In addition to beads and pins, the site

produced a soapstone vessel shard, a soapstone

loom weight, spindle whorls of both soapstone and

sandstone, and a variety of other domestic objects

(Figs. 11–12, 14–15). These are consistent with

“normal” occupation, perhaps by both men and

women, rather than use as either a temporary refuge

or a monastery. Textile making is associated with

women in late Viking Age sources such as the poem

Darraðarljóð incidentally set in Scotland in Njáls

saga (Magnusson and Pálsson 1960, Poole 1993).

The absence of elaborate stone sculpture

incorporating Christian motifs,

even from the previous excavation in

the churchyard, should also be noted

(albeit with the weakness of negative

evidence). Excavated early medieval

monasteries in Scotland produce

monuments of this kind (e.g., Carver

2008, Lowe 2008). Lastly, the burial

evidence from the cemetery is inconsistent

with an exclusively ecclesiastical

function. Of the six excavated

graves, fi ve were of children, one of

which was newborn (Morris and Emery

1986). At least two of these infant

graves are associated with the earliest

phase of the chapel.It seems likely that

families were living in the settlement

on the Brough of Deerness.

The number of burials around the

chapel is unusually small. It could

therefore not have been in use for

the full duration of occupation on the

Brough of Deerness (given that the latter

is now known to potentially extend

from the 6th to the 12th century). A date

before the 10th century is also unlikely

for a chapel of this kind, based on comparative

grounds (cf. Blair 2005). If it

was only used during the last two cen-

(Fig. 14) and a roughly incised spindle whorl (Fig.

15) were lost in the building.

There were no shell holes in Area B, although

occasional pieces of possible shell casing were recovered.

Bone was not preserved in this area, with

the exception of a few pieces in the ash of a hearth.

The sediments were probably too acid—presumably

because the cultural deposits are shallower in Area B

than in Area A and thus do not adequately buffer the

naturally high pH. It may also be relevant, however,

that House 20 is so close to the cliff-edge. Presumably,

much household refuse would have been discarded

directly into the sea.

Discussion

The 2008 trial excavation at the Brough of Deerness

set out to explore the state of preservation, chronology

and function of the site and thus to evaluate

its implications for the study of power, ideology, and

migration/transnationalism in the early historic period.

The preliminary results are illuminating. Firstly,

the settlement is remarkably well preserved despite

records of shelling for target practice during both

the First and Second World Wars. Wall foundations,

house fl oors, and middens are largely intact. In the

excavated areas, shell holes are few (only one thus

Figure 15. A roughly incised spindle whorl from House 20 in Area B (scale

in cm). Photograph © James Barrett.

92 Journal of the North Atlantic Volume 2

might speculate that these hypothetical chieftains

espoused different religions as their ideological

bases of power (Barrett 2002). The latest possible

pagan burials in Orkney Mainland—particularly

one at Buckquoy coin-dated to the mid-10th century

(Ritchie 1977)—come from the Birsay area. Following

this third hypothesis, it would have been highly

symbolic that Birsay became Orkney’s episcopal

center in the mid-11th century. The bishopric was

established by Earl Thorfi nn (Guðmundsson 1965,

Tschan 1959), the son of Sigurd Hlodvisson, who is

the fi rst Orkney earl whose existence is historically

indisputable. Sigurd died, perhaps under a (pagan?)

raven banner, at the Battle of Clontarf in Ireland in

1014 (Guðmundsson 1965, Hennessy 1998).

Regardless of whether this third hypothesis is

correct, it is clear from the Brough of Deerness and

the Brough of Birsay that the adoption of Christianity,

rather than the maintenance of paganism, was an

important corollary of chiefl y power in Orkney by

the late Viking Age. Of course, this observation applies

for most areas of Northern Europe at much the

same time (e.g., Carver 2002). Depending on how

early it began, however, the association between

chieftains and Christian practice may be the most

lasting evidence for indigenous infl uence on migrant

Scandinavian elites in early historic Scotland.

Acknowledgments

Further details regarding the 2008 Brough of Deerness

excavation can be found in the on-line annual report

(Barrett and Slater 2008) and in a popular article on the

results published in issue 228 of the magazine Current

Archaeology. The excavation was conducted with the

permission of Historic Scotland and the Orkney Islands

Council. It was jointly funded by the McDonald Institute

for Archaeological Research, the Orkney Islands Council,

the Royal Norwegian Embassy (London), and the Norwegian

Consulate General (Edinburgh). Contributions in

kind were generously provided by Orkney College and the

Orkney Museum. Special thanks are owed to Julie Gibson

(Orkney Archaeologist), Christine Skene (Orkney Islands

Council), Anne Brundle (Orkney Museum), Anne Billing

and Isobel Gardner (of The Friends of St Ninian’s), Allan

Rutherford (Historic Scotland), and Christopher Morris

(University of the Highlands and Islands Millennium Institute)

for helping make the project happen. The excavation

crew included Tom Blackburn, Fiona Breckenridge,

Pieterjan Deckers, Paul Ewonus, Katie Hall, Vicki Herring,

Janis Mitchell, Brian Rahn, and Leanne Zeki. James

Graham-Campbell kindly assisted with interpreting the

artifacts. Donna Surge and Michael Mobilia of the University

of North Carolina provided valuable observations

regarding the geology of the Brough. Judith Jesch and

Clare Downham helped encourage this work in its early

stages. Lord Wallace of Tankerness, Morag Robertson,

Stein Iversen, and Mona Røhne generously assisted with

fund-raising. Last but not least, the residents of Deerness

have generously welcomed us onto their lands and into

their heritage.

turies (plus or minus) of occupation, as seems likely,

the small number of associated graves implies either

that the late Viking Age settlement on the Brough

was not continuous, that only a select few (perhaps

members of a single elite family) had burial rights

there, or a combination of these factors.

Given these observations, how might one interpret

the function of the settlement? Hypotheses

regarding possible pre-Viking Age monastic occupation

of “Celtic” type would be very premature,

given that we have just begun to clarify the top of the

sequence which is late Viking Age. The deep stratigraphy

and radiocarbon dates do indicate earlier occupation

levels, but nothing can yet be said about the

character of these phases. Conversely, monasticism

is unlikely for the excavated Viking Age settlement

because the archaeological record from both the past

and present excavations suggests habitation by family

groups and lacks ecclesiastical sculpture.

If not monastic, what was the nature of the settlement?

Christopher Morris (e.g., 1990, 1996a) has

suggested that it should be interpreted as a chiefl y

stronghold with a private chapel, a possibility that

is supported by the new excavation and the obvious

defensive qualities of the site’s location. But how

would a settlement of this type have functioned

within its wider community? Three tentative models

can be proposed.

First, it is possible that the site was one of several

centers used by the earls of Orkney in a peripatetic

system by which they lived off the proceeds of scattered

estates (cf. Alcock 1988, Ralston 2004). Produce

could have been brought to the stack from, for

example, neighboring Viking Age settlements such as

those known at Skaill (Buteux 1997) and Newark Bay

(Barrett et al. 2000, Brothwell 1977). In this eventuality,

the Brough of Deerness would presumably have

been permanently garrisoned, but only occasionally

fully inhabited. If this hypothesis is correct, the site

can perhaps be seen as a rough equivalent of the better-

known elite center of the Brough of Birsay, with

its church and associated settlement. Second, the site

could represent the stronghold of a wealthy magnate

below the level of earl, of the kind well known from

the Orkneyinga saga (Barrett 2007). In this event, the

Brough of Deerness might be imagined as an imitation

or emulation of Birsay.

Alternatively, if the earldom of Orkney was not

established until the early 11th century, as is possible

based on the contemporary historical and archaeological

evidence rather than the later Orkneyinga

saga (Barrett 2008b, Woolf 2007), the Brough of

Birsay and the Brough of Deerness could represent

the strongholds of competing independent chieftains.

Given the possible 10th-century foundation

of the chapel on the Brough of Deerness, and of

a nearby Christian cemetery at Newark Bay, one

2009 J. Barrett and A. Slater 93

tations of so-called souterrains. Bulletin of the Institute

of Archaeology 14:179–90.

Buteux, S. (Ed.) 1997. Settlements at Skaill, Deerness,

Orkney. British Archaeological Reports British Series

260. Archaeopress, Oxford, UK. 276 pp.

Carver, M. (Ed.) 2002. The Cross Goes North. Boydell

Press, Woodbridge, UK. 602 pp.

Carver, M. 2008. Portmahomak: Monastery of the Picts.

Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, Scotland,

UK. 232 pp.

Crawford, B.E. 2005. Thorfi nn, Christianity, and Birsay:

What the saga tells us and archaeology reveals. Pp.

88–110, In O. Owen (Ed.). The World of Orkneyinga

Saga: “The Broad-cloth Viking Trip.” The Orcadian,

Kirkwall, Scotland, UK. 232 pp.

Curle, C.L. 1982. Pictish and Norse Finds from the Brough

of Birsay 1934–74. Society of Antiquaries of Scotland

Monograph Series Number 1. Society of Antiquaries

of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK. 141 pp.

Dumville, D.N. 2002. The North Atlantic monastic thalassocracy:

Sailing to the desert in early medieval insular

spirituality. Pp. 121–30, In B.E. Crawford (Ed.). The

Papar in the North Atlantic: Environment and History.

St. John's House Papers No. 10, University of St. Andrews,

St. Andrews, Scotland, UK. 447 pp.

Forsyth, K. 1995. The ogham-inscribed spindle whorl

from Buckquoy: Evidence for the Irish language in

pre-Viking Orkney? Proceedings of the Society of

Antiquaries of Scotland 125:677–96.

Freke, D. (Ed.) 2002. Excavations on St Patrick’s Isle,

Peel, Isle of Man, 1982–88: Prehistoric, Viking, Medieval,

and Later. Liverpool University Press, Liverpool,

UK. 405 pp.

Gestsson, G. 1959. Gröf í Öræfum. Árbók hins íslenzka

fornleifafélags 1959:5–87.

Gifford, J. 1992. The Buildings of Scotland: Highlands

and Islands. Penguin Books in association with The

Buildings of Scotland Trust, London, UK. 688 pp.

Guðmundsson, F. (Ed.) 1965. Íslenzk fornrit 34. Orkneyinga

saga. Hið íslenzka fornritafélag, Reykjavík,

Iceland. 428 pp.

Hennessy, W.M. (Ed.) 1998. Annals of Ulster, Volume I.

Éamonn de Búrca, Dublin, Ireland. 269 pp.

Hunter, J.R. 1986. Rescue Excavations on the Brough of

Birsay 1974–82. Society of Antiquaries of Scotland

Monograph Series Number 4. Society of Antiquaries,

Edinburgh, Scotland, UK. 230 pp.

Hvass, S. 1993. Bebyggelsen. Pp. 187–94, In S. Hvass and

B. Storgaard (Eds.). Da Klinger i Muld: 25 års arkæologi

i Danmark. Aarhus Universitetsforlag, Aarhus,

Denmark. 312 pp.

Lamb, R.G. 1973. Coastal settlements of the north. Scottish

Archaeological Forum 5:76–98.

Lamb, R.G. 1980. Iron Age promontory forts in the

Northern Isles. British Archaeological Reports British

Series 79, Oxford, UK. 102 pp.

Lowe, C. (Ed.) 2008. Inchmarnock: An Early Historic

Monastery and its Archaeological Landscape. Society

of Antiquaries of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK.

313 pp.

Magnusson, M., and H. Pálsson. 1960. Njal's Saga. Penguin,

London, UK. 384 pp.

Literature Cited

Alcock, L. 1988. The activities of potentates in Celtic

Britain, A.D. 500–800: A positivist approach. Pp.

22–46, In S.T. Driscoll and M.R. Nieke (Eds.). Power

and Politics in Early Medieval Britain and Ireland.

Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, Scotland,

UK. 200 pp.

Alcock, L. 2003. Kings and Warriors, Craftsmen and

Priests in Northern Britain A.D. 550–850. Society of

Antiquaries of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK.

460 pp.

Anonymous. 2003. Extreme Archaeology: Kame of Isbister,

Shetland Islands. HU 38279152 Archaeological

Evaluation Data Structure Report. Mentorn TV, London,

UK.

Barrett, J.H. 2002. Christian and pagan practice during the

conversion of Viking Age Orkney and Shetland. Pp.

207–26, In M. Carver (Ed.). The Cross Goes North.

Boydell Press, Woodbridge, UK. 602 pp.

Barrett, J.H. 2007. The pirate fi shermen: The political

economy of a medieval maritime society. Pp. 299-340,

In B.B. Smith, S. Taylor, and G. Williams (Eds.). West

Over Sea: Studies in Scandinavian Sea-borne Expansion

and Settlement Before 1300. Brill, Leiden, The

Netherlands. 586 pp.

Barrett, J.H. 2008a. What caused the Viking Age? Antiquity

82:671–85.

Barrett, J.H. 2008b. The Norse in Scotland. Pp. 411–27,

In S. Brink, and N. Price (Eds.). The Viking World.

Routledge, London, UK. 717 pp.

Barrett, J.H., and M.P. Richards. 2004. Identity, gender,

religion, and economy: New isotope and radiocarbon

evidence for marine resource intensifi cation in early

historic Orkney, Scotland. European Journal of Archaeology

7:249–271.

Barrett, J., and A. Slater. 2008. The Brough of Deerness

Excavations 2008: Research context and data structure

report. Unpublished report. McDonald Institute

for Archaeological Research, Cambridge, UK. Available

online at www.mcdonald.cam.ac.uk/projects/

Deerness/Brough_of_Deerness_2008.pdf. Accessed

September 21, 2009.

Barrett, J.H., R.P. Beukens, and D.R. Brothwell. 2000.

Radiocarbon dating and marine reservoir correction of

Viking Age Christian burials from Orkney. Antiquity

74:537–43.

Barrowman, R.C. 2008. Splendid isolation? Changing

perceptions of Dùn Èistean, an island on the north

coast of the Isle of Lewis. Pp. 95–111, In G. Noble, T.

Poller, J. Raven, and L. Verrill (Eds.). Scottish Odysseys:

The Archaeology of Islands. Tempus, Stroud,

UK. 180 pp.

Barrowman, R.C., C.E. Batey, and C.D. Morris. (Eds.)

2007. Excavations at Tintagel Castle, Cornwall,

1990–1999. Society of Antiquaries of London, London,

UK. 370 pp.

Batey, C.E. 1991. Archaeological aspects of Norse settlement

in Caithness, North Scotland. Acta Archaeologica

61:29–35.

Blair, J. 2005. The Church in Anglo-Saxon Society. Oxford

University Press, Oxford, UK. 604 pp.

Brothwell, D. 1977. On a mycoform stone structure in

Orkney, and its relevance to possible further interpre94

Journal of the North Atlantic Volume 2

Moore, J. 2007. Brough of Deerness. Discovery and Excavation

in Scotland, New Series 7:125.

Moore, H., and G. Wilson. 1998. Orkney Coastal Zone

Assessment Survey 1998. EASE Archaeological Consultants,

Edinburgh, Scotland, UK. 344 pp.

Morris, C.D. 1990. Church and Monastery in the Far

North: An archaeological evaluation. Jarrow Lecture

1989. St Paul’s Church, Jarrow, UK. 43 pp.

Morris, C.D. 1996a. Church and monastery in Orkney and

Shetland: An archaeological perspective. Pp. 185–206,

In J.F. Krøger and H. Naley (Eds.). Nordsjøen: Handel,

Religion og Politikk. Karmøy Kommune, Kopervik,

Norway. 211 pp.

Morris, C.D. 1996b. From Birsay to Tintagel: A personal

view. Pp. 37–78, In B.E. Crawford (Ed.). Scotland in

Dark Age Britain. Scottish Cultural Press, Aberdeen,

Scotland, UK. 160 pp.

Morris, C.D. (Ed.) 1996c. The Birsay Bay Project Volume

2: Sites in Birsay Village and on the Brough of

Birsay, Orkney. University of Durham, Department of

Archaeology Monograph Series Number 2. University

of Durham, Durham, UK. 302 pp.

Morris, C.D., and N. Emery. 1986. The chapel and enclosure

on the Brough of Deerness, Orkney: Survey and

excavations, 1975–1977. Proceedings of the Society

of Antiquaries of Scotland 116:301–74.

Norr, S., and D. Fewster. 2003. Borg II. Pp. 109–18, In

G.S. Munch, O.S. Johansen, and E. Roesdahl (Eds.).

Borg in Lofoten: A Chieftain’s Farm in North Norway.

Tapir Academic Press, Trondheim, Norway. 309 pp.

O’Sullivan, J. 1999. Iona: Archaeological investigations

1875–1996. Pp. 215–43, In D. Broun and T.O. Clancy

(Eds.). Hope of Scots: Saint Columba, Iona, and

Scotland. T. and T. Clark, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK.

314 pp.

Ovenden, S. 2008. Geophysical survey. Pp. 7–8, In J.

Barrett and A. Slater (Eds.). The Brough of Deerness

Excavations 2008: Research context and data structure

report: 7–8. Unpublished report. McDonald Institute

for Archaeological Research, Cambridge, UK. Available

online at www.mcdonald.cam.ac.uk/projects/

Deerness/Brough_of_Deerness_2008.pdf. Accessed

September 21, 2009.

Poole, R. 1993. Darraðarljóð. Pp. 121, In P. Pulsiano

(Ed.). Medieval Scandinavia. Routledge, London, UK.

792 pp.

Ralston, I. 1997. Pictish homes. Pp. 19–34, In D. Henry.

The Worm, the Germ, and the Thorn: Pictish and Related

Studies Presented to Isabel Henderson. The Pinkfoot

Press, Balgavies, Angus, Scotland, UK. 200 pp.

Ralston, I. 2004. The Hill-forts of Pictland since “The

Problem of the Picts.” Groam House Museum, Rosmarkie,

Scotland, UK. 53 pp.

Ritchie, A. 1977. Excavation of Pictish and Viking-Age

farmsteads at Buckquoy, Orkney. Proceedings of the

Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 108:174–227.

Tschan, J. (Ed.) 1959. Adam of Bremen. The Archbishops

of Hamburg Bremen. Columbia University Press, New

York, NY, USA. 288 pp.

Woolf, A. 2007. From Pictland to Alba 789–1070. Edinburgh

University Press, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK.

320 pp.